Imagine 1977, sitting at the helm of one of your very first personal computers. The Commodore “Personal Electronic Transactor,” endearingly nicknamed the PET, promised to be an all-in-one “bookkeeper, cook, language tutor, inventory clerk, and playmate.” For the first time, you could type up programs on the tiny “chiclet” keyboard — working out your math homework, saving snippets of recipes, designing simple graphics — and see the results spring up before your eyes. Unlike a washing machine or a calculator, here was a first encounter with a machine that was fundamentally open-ended, dynamic, and responsive in a tangible way.

The sheer magic of this experience is hard to imagine for most of us now that the personal computer is essential, almost mundane. But it didn’t start out this way. For three decades, the computer existed only at the fringes of society, operated by obsessive programmers in the secluded halls of academia and technology corporations.

For three decades, programmers wrote up their programs on coding sheets and brought them down to the lab to get punched into a deck of cards. They’d carry their box of punch cards to the computer operator’s office, whose job was to feed the cards into the giant mainframe a batch at a time. They could come back for a printout of their results the next day, which often told them, sorry, “Compile error on line 21,” better luck next time.

The first computers were powerful, but no more than efficient arithmetic calculators. Early visionaries like J.C.R. Licklider began to see past the short-sightedness of the punch card “batch processing” machine:

While everyone else was investing in ever-faster batch processing mainframes, Licklider recognized the potential for new paradigms of interaction to enable fundamentally different applications for computers, and fundamentally different roles for them in our lives. Envisioning the possibility of having “a graphics display that allowed you to see the model’s behavior—and then if you could somehow grab the model, move it, change it, and play with it interactively—” Licklider concluded, “then the experience of working with that model would be very exciting indeed.”

The vision of early computing pioneers like Licklider forms the foundation for everything we do today. Can you imagine operating a computer without the graphical windows, buttons, and interfaces we have today? Can you picture navigating a new topic without hypertext links, where clicking on a blue piece of text instantly allows you to access related information? Can you envision computers without the idea of “clicking” on something in the first place, acting in the digital world by tapping your index finger on a mouse?

These were all new concepts when they were invented, foreign in the frame of history. So many things we can do with computers today were enabled not just by making computers more advanced or more powerful, but by rethinking the modes by which humans could interact with machines.

We’ve now returned to the age of batch processing — not with computers, but with the new wave of “intelligent” applications, driven by artificial intelligence and machine learning.

But we’re still working with the equivalent of primitive knobs, dials and punch cards, programming machine learning systems to do what we want by labeling millions of training examples.

We’re still waiting around to pick up the fan-folded printout the next day, without ways to interact and give feedback to machine learning systems.

We still think of humans as oracles of intelligence whose main purpose in these systems is to label the right answer. We haven’t noticed, as Alan Kay said in 1989, “not just that end users had functioning minds, but that a better understanding of how those minds worked would completely shift the paradigm of interaction.” In other words, considering how humans think and work can completely shift how we design systems.

While there is much excitement about the possibility for new “intelligent” applications to transform our lives, we haven’t quite seen it happen at a large scale. Self-driving cars have been promised — and delayed — for decades, and “intelligent” agents like Siri or Alexa aren’t yet good enough to make our lives drastically different. People focus on collecting better datasets or building more sophisticated models, but what if part of the opportunity is lost in the lack of novel interactive paradigms for machine learning, ways for people to use these systems in more flexible ways than we’re currently envisioning?

Andrej Karpathy likened modern machine learning to Software 2.0, “the beginning of a fundamental shift in how we write software.” Whereas “traditional software” is limited to exactly the set of instructions that the programmer specifies, the behavior of machine learning-powered software is driven by data. We can train a self-driving car to identify a pedestrian just by showing it examples, without ever explicitly programming how to identify one from a picture. Our technology today can extend beyond what a programmer specifies, making it more powerful and open-ended than ever before.

This means that we’ll face new hazards when we fail to design the right modes of interaction with humans. Machine learning systems won’t simply crash when given unexpected inputs, or when used improperly. They will act in unpredictable ways: a self-driving car can swerve out of the lane when a car approaches at an odd angle, or a newsfeed algorithm can have the unintended consequence of showing increasingly polarizing content. If we don’t design for human interaction, we will find ourselves with less and less control over the technology that governs our lives.

On the other hand, there’s reason for excitement, with new ways to give feedback to our tools, understand the world, and augment our thinking.

This essay will explore some of the possibilities to rethink how humans and “intelligent” machines interact today. The focus is on practical application — how can technology that exists today be leveraged creatively to make applications that are vastly more powerful and useful?

I / The state of human-AI interaction

The allure of modern machine learning is that it often just works — collect a large dataset, feed it through a giant model, and it somehow learns to do the task. It could be as simple as identifying objects in images or as complicated as playing Go. The “unreasonable effectiveness of data,” combined with computing power, makes it possible for machine learning to accomplish things that we didn’t think possible.

In the best case, ML is akin to a “Big Red Button” — press the button, and it learns to accomplish a specific task, while hiding a lot of the complexity (for better or worse!).

Machines aren’t yet as intelligent as humans, however. The real world is messier than the neat sandboxes of research; even if a self-driving car can recognize pedestrians with 99% accuracy in simulation, it might still hit the woman crossing the road “because it kept misclassifying her”. As we begin to push the boundaries of what machines are capable of, it’s clear that we still need humans to be part of the process. Given that self-driving cars aren’t yet capable of driving fully autonomously, we put human operators behind the wheel, ready to take control if things go wrong.

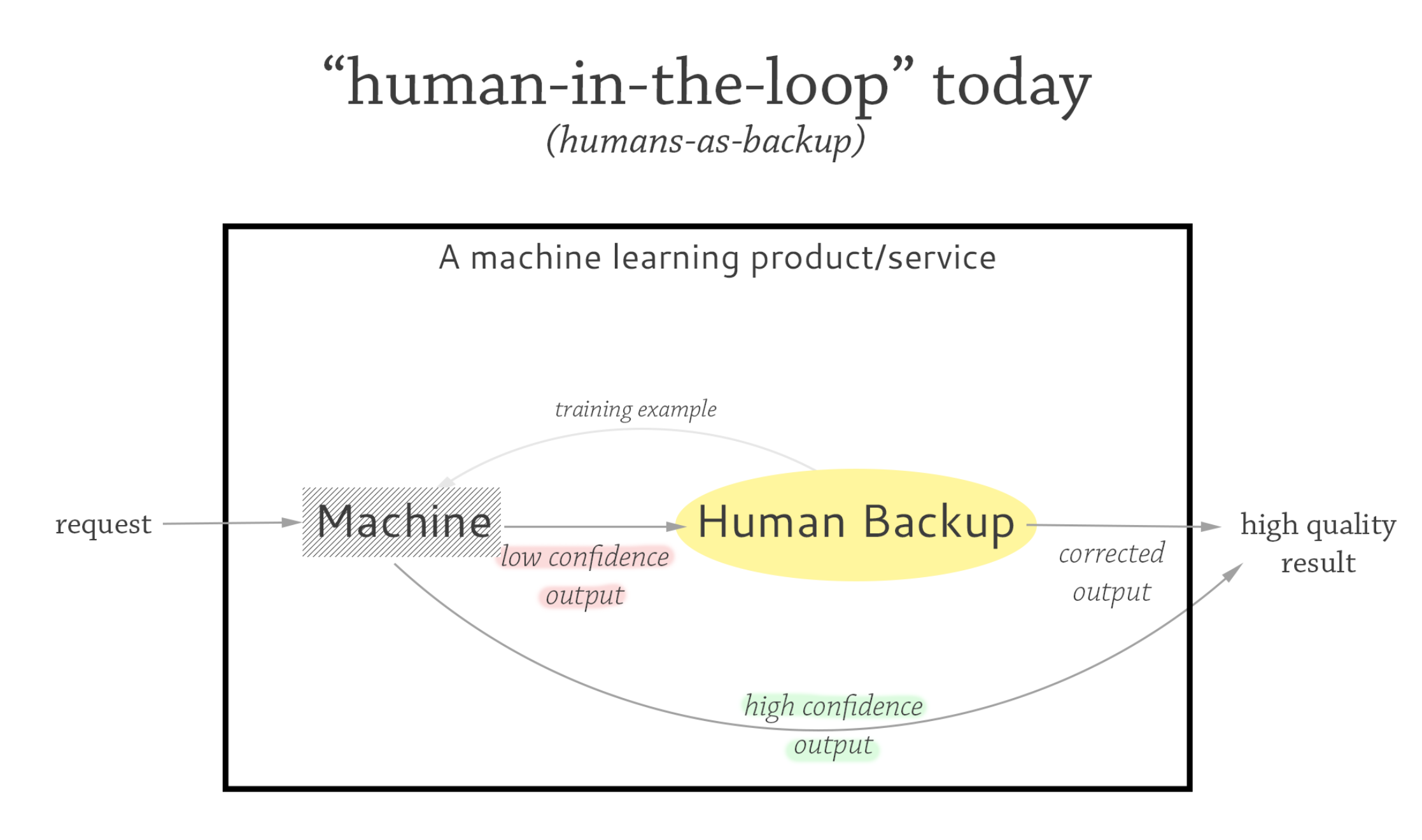

We need hybrid human-AI systems, and the most common way to involve humans is to have them act as a fallback. A so-called human-in-the-loop system today often means a specific kind of way of involving a human: the machine makes a first pass at a task, and if it fails, the human takes over.

This interaction paradigm — which we’ll call humans-as-backup (to distinguish it from other human-in-the-loop paradigms) — is just one way to involve humans in the loop, but it’s taken for granted as a general principle to be applied in any case where machines fall short. In autonomous driving, the car drives on its own until a human operator takes control in difficult conditions. In customer service, a machine attempts to process a request until it doesn’t understand any more, passing it over to a human agent. In legal tech, a machine makes a first pass at reviewing a contract; a lawyer looks over the rest.

Humans-as-backup is, by far, the most common arrangement of humans and machines. One of the main reasons why is because it’s the clearest path to work up to Big Red Button systems. We get to collect data for free in this workflow: a self-driving car can drive most of the time, but on exactly the road conditions it can’t handle, we can observe and collect data from the human driver. The hope is that as we collect more data and the machine does better, we wean off the humans-as-backup and move into full autonomy.

But it doesn’t work quite as efficiently in practice.

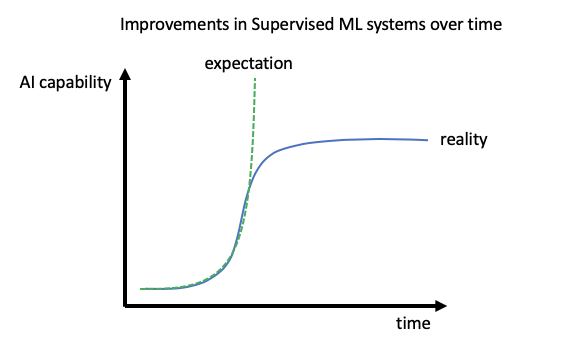

ML companies face scaling challenges when they realize the edge cases are thornier than expected. Autonomous trucking company Starsky Robotics recently closed shop, concluding that “supervised machine learning doesn’t live up to the hype”:

As noted by venture capital firm a16z, humans in the loop — again, most often with humans-as-backup — are more or less taken for granted as a necessity for functioning at a high level of accuracy. Real systems like Facebook’s content moderation algorithms are constantly faced with new contexts, whether it’s the latest offensive meme or a change in cultural discourse. Shifting standards require new training data (labeled by humans) to be continuously fed back into the system. So although humans-as-backup are imagined to merely be a stepping stone to Big Red Button systems, they end up de facto as the permanent mode of operation.

Then we’re faced with a human problem: while humans-as-backup may work temporarily for data collection, in the long run, humans aren’t made to work in these kinds of situations. We can’t expect humans to perform at their best in the context of a process designed for machines. In autonomous driving, humans are expected to take control right before a difficult situation. As the American Bar Association noted, there are a number of human factors in how successful the driver is at managing the situation: roadway conditions, how and when he is alerted to the fact that the current situation is beyond the car’s capabilities, how quickly he can gather information, and how the machine performs the handoff. In practice, braking reaction time of drivers using automation is up to 1.5 seconds longer than drivers manually operating the vehicle, or as long as 25 seconds if they’re doing a secondary task (e.g. reading a text, primed with the expectation that the vehicle can handle driving on its own). The hope was always that autonomous cars would be much safer than human drivers, but combining the two results in the worst of both worlds.

It seems counterintuitive, but doctors, lawyers, and other domain experts we integrate into these systems may be less efficient when forced to operate in the context of a humans-as-backup system. The system is primarily designed to collect data and to maintain the illusion of autonomy for as long as possible; the human interface is an afterthought.

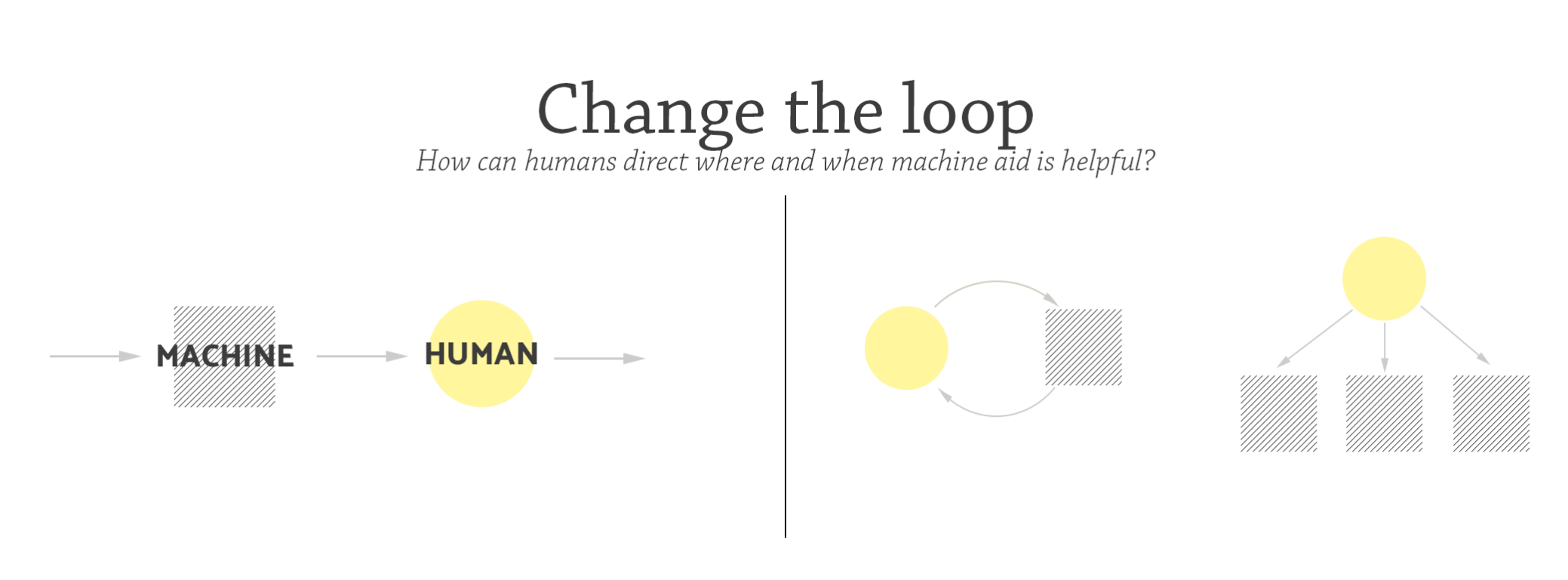

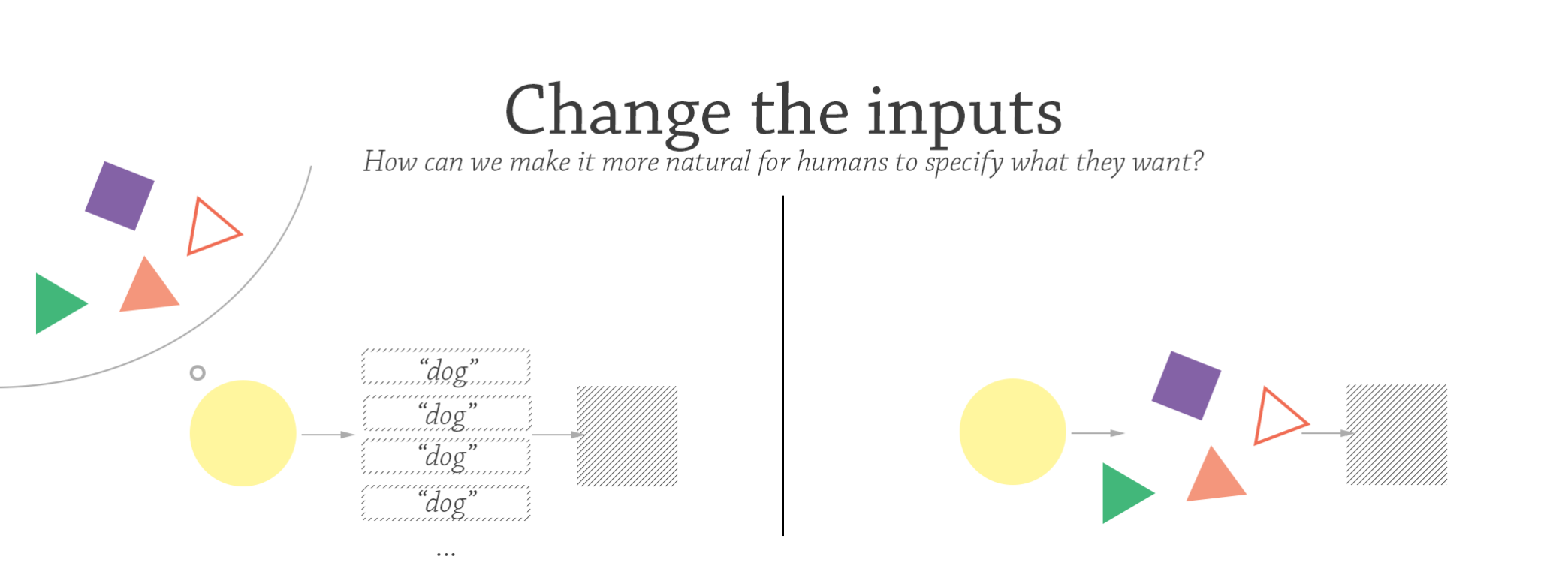

Humans-as-backup as the dominant paradigm of human-machine collaboration is limiting our imagination. It suggests that the only way we can give feedback (if at all) to machines is to label data points as examples of what we want. It embodies the idea that the only way for machines to help humans is to do the easy tasks for them, leaving the hard cases up to the human. But there are actually other ways we can imagine, too: what if humans + machines together could seamlessly handle all the work? Or, what if machines could help us do hard things better, even if they aren’t able to do them on their own?

These questions suggest new directions for human-AI interaction to consider:

- Change the loop: how can humans direct where / when machine aid is helpful?

- Change the inputs: how can we make it more natural for humans to specify what they want?

- Change the outputs: how can we help humans understand and solve their own problems?

II / New Directions

Change the loop

Mixed-initiative

In human-in-the-loop systems today, the human plays a secondary role as a fallback when the machine doesn’t know what to do. What would it look like if we embraced humans in the loop as a feature, not a bug? In problems where the machine doesn’t do well enough on its own, we might instead design the system for humans to make use of the machine in more flexible ways.

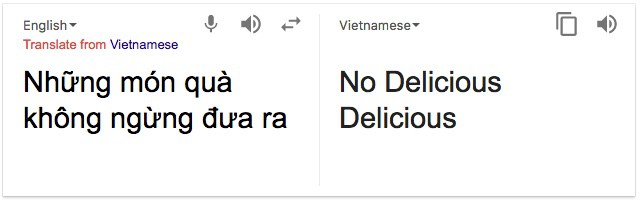

Machine translation (MT) is probably one of machine learning’s best examples of “good, but not good enough.” Google Translate makes eating in a foreign country and understanding the menu a superpower that we take for granted in the 21st century. Yet for anyone who’s ever optimistically used Google’s “Translate this page” function across the Internet, these automated methods are still often laughably incoherent:

For most content that needs to be internationalized, fully automated translations simply aren’t good enough. While we can use MT to translate simple phrases when we travel, the translation problem for the long tail of difficult-to-translate content is conceptually different — e.g. for company branding material, legal contracts, pharmaceutical directions, technical manuals, or literature. Reliably translating 90% of everyday phrases like “I want to order fish” requires a small vocabulary and a basic understanding of grammar that a machine learning model could infer from statistical relationships, given a large body of text. Translating “Contractor will remain owner of the rights to the work resulting from the services for this agreement, but gives Company the rights to use and distribute the work,” on the other hand… well, it’ll take more than a 3rd grader’s grasp of language rules to understand and precisely describe the nuances of the relationship here.

There’s an obvious way to integrate human oversight into MT systems—namely, the current “human-in-the-loop” way. We can imagine having the machine “pre-translate” the document, and then presenting it to a human translator to go in and correct any awkward or unnatural phrases, like a proofreader. In the translation industry, this is called “post-editing.”

But as it turns out, using machine translation as your starting point produces markedly different kinds of results. Even if a human post-edits the result, the translations are noticeably more unnatural, more machine-like. Researcher Douglas Hofstadter compares Google Translate (as of 2018) to a fluent German speaker (himself) in “The Shallowness of Google Translate”:

Imagine yourself post-editing the Google Translate output. The beginning of the sentence starts out reasonably accurate, albeit awkward. The phrase “lost war” kind of works, but it takes some effort to search through the mental thesaurus for something better. But by the end of the passage it has totally missed the focus on the exclusion of female scientists (according to Hofstadter, due to its failure to understand “that the feminizing suffix “-in” was the central focus of attention in the final sentence. Because it didn’t realize that females were being singled out, the engine merely reused the word scientist…”). It needs a total rework, better done from scratch.

Even worse, imagine the translations you wade through for the rest of the document, littered with “German-National” and awkward phrasing structures you fix over and over again. It’s no surprise that translators hate post-editing, a uniquely tedious and vaguely degrading process. As Brown University Professor Robert Beyer recounted of his experience translating scientific papers from Russian to English:

Although post-editing might be faster, and perhaps cheaper, the quality of the results still falls short of human translation.

But there is an alternative: instead of post-editing a machine output, what if we opted for interactive, mixed-initiative translation — i.e., where the human and the machine take turns in directing the work?

If we flip the paradigm and instead have humans initiating the translation, with the machine providing helpful, “Google Smart Reply”-like completions, we get a totally different experience. The translator has the creative freedom to start the sentence a different way, and the automatic translation can adapt on-the-fly. And if the translation is a standard, repetitive sort of phrase, the translator can simply plug it in and move on.

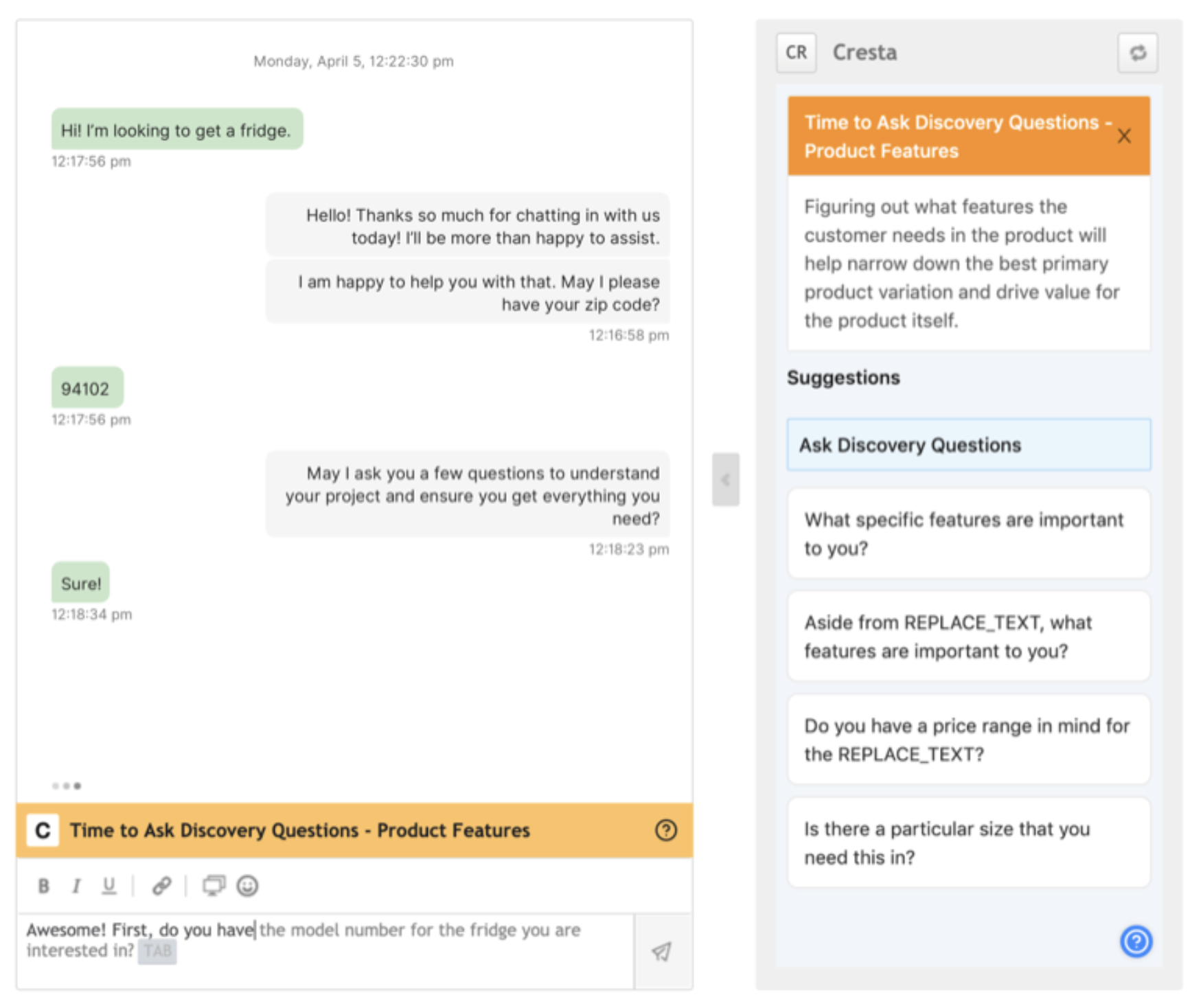

In a mixed-initiative loop, the human seamlessly decides which easy examples to delegate to the machine and which need to be handled manually. All the output is guaranteed to be high-quality, but we still get the efficiency and cost benefits up to the limit of what the technology is capable of. The same pattern can be used in other contexts. The common approach to modernizing customer service is to build chatbots that handle common requests, with humans-as-backup. Unfortunately, just like translation, canned conversations are easy, but there is a long tail of open-ended dialogue contexts that are still too difficult for machines. In 2017, after seeing that its bots had a 70% failure rate, Facebook announced that its engineers would shift to “training [Messenger] based on a narrower set of cases so users aren’t disappointed by the limitations of automation.” Like with translation, the best approach might be to ditch the hope of vastly improved language understanding and instead reap gains from making customer service agents vastly more efficient with what we can do with machines today.

Building systems around existing human workflows actually makes it easier for companies like Lilt (mixed-initiative translation) and Cresta (mixed-initiative contact centers) to continuously improve their ML models. As translators or agents continue to work, you continue to collect high-quality, expert-annotated data, as well as more fine-grained data from the interactions themselves (knowing that a translator was prompted with word A but deliberately chose word B tells us something!).

From here, there’s a whole new realm of possible experiences: the ability to provide users relevant information or context at the precise moment it’s useful, to learn user behavior and preferences at a more fine-grained level, and to adapt to new content on-the-fly.

Human-initiated

Translation exposes how starting with a human process and building tooling to support the human produces qualitatively different results than starting with an automated process and adding humans in order to catch the edge cases. This lesson is especially apt today, when ML systems are great but not perfect.

But even as machine learning achieves “superhuman accuracy” on task after task (as ML researcher Andrej Karpathy details in his post on competing with a computer vision system), the lesson is still worth remembering. Real-world constraints are rarely fully encoded into the system. In translation, a marketing customer might want more fun, colloquial language, while a healthcare company might require fine distinctions between clinical terms. The real objective is not just achieving 100% accuracy on the test set (as machine learning is trained to do), but producing quality content that actually meets the needs of the particular circumstance.

Interactive optimization addresses this very problem — even when the task at hand is a standard algorithmic problem (e.g. scheduling, vehicle routing, resource optimization), there are applications where users might want to steer the algorithm based on their preferences and knowledge of real-world constraints:

Interactive optimization algorithms like human-guided search (HuGS) provide mechanisms for people to provide these “soft” constraints and background knowledge by adding constraints as the search evolves or intervening by manually modifying computer-generated solutions. Not only do humans develop more trust in these systems, they can also produce objectively higher-performing solutions than the computer alone. As the researchers observe, “it took, on average, more than one hour for unguided search to match or beat the result of 10 minutes of guided search.”

Modern machine learning is more sophisticated than simple search algorithms, but the same dynamics apply, and ideas from interactive optimization are just as helpful. A human in control of a machine learning loop can use their knowledge of context to guide the machine, triage problems, and select the right tools.

In freestyle chess, where humans are allowed to consult external resources and use chess AI engines at will, human-machine teams consistently win out over pure AI players. These so-called “centaurs’’ use their computers to evaluate the strength of potential candidate moves, consult databases of openings, and eliminate blunders. When the machine’s advantage in memorization and brute-force planning is equalized, freestyle chess becomes a true test of strategy, decision-making and judgment.

In 2005, a amateur team called ZachS, aided by several chess engines running on consumer hardware, defeated grandmaster Vladimir Dobrov using a computer of his own. They were a soccer coach and a database administrator from New Hampshire, with an underwhelming ELO of 1381 and 1685 each (Dobrov’s was 2600+). When asked how the two of them did it, they said:

A superior understanding of when and how to use machine assistance led them to the victory. And again, it wasn’t with a humans-as-backup loop, but with a process constructed to prioritize human judgment in directing the machine.

On reviewing some of the modern failures of AI — systems learning, incorrectly, to use confounding factors in medical diagnosis, for example — we might be reminded of ZachS:

ML is just a tool, one whose strengths and weaknesses need to be properly understood by the user. As designers of those systems, we would do best to define usage patterns where humans iteratively refine an output instead of assuming machines will provide “the answer,” and preserve maximum flexibility to direct tools to where they are most helpful.

Change the inputs

Concepts

Physicist and author Ursula Franklin first introduced the idea of “technology as practice” in 1989, pointing out that technology is not a set of gadgets or artifacts, but a system that dictates a particular mindset, organization, and set of procedures. As she notes in The Real World of Technology:

We’ve seen already how modern machine learning has dictated a particular sort of loop. It also encodes a particular formulation of the problem that might not always align with the mental models that humans already have. Says Google research scientist Been Kim:

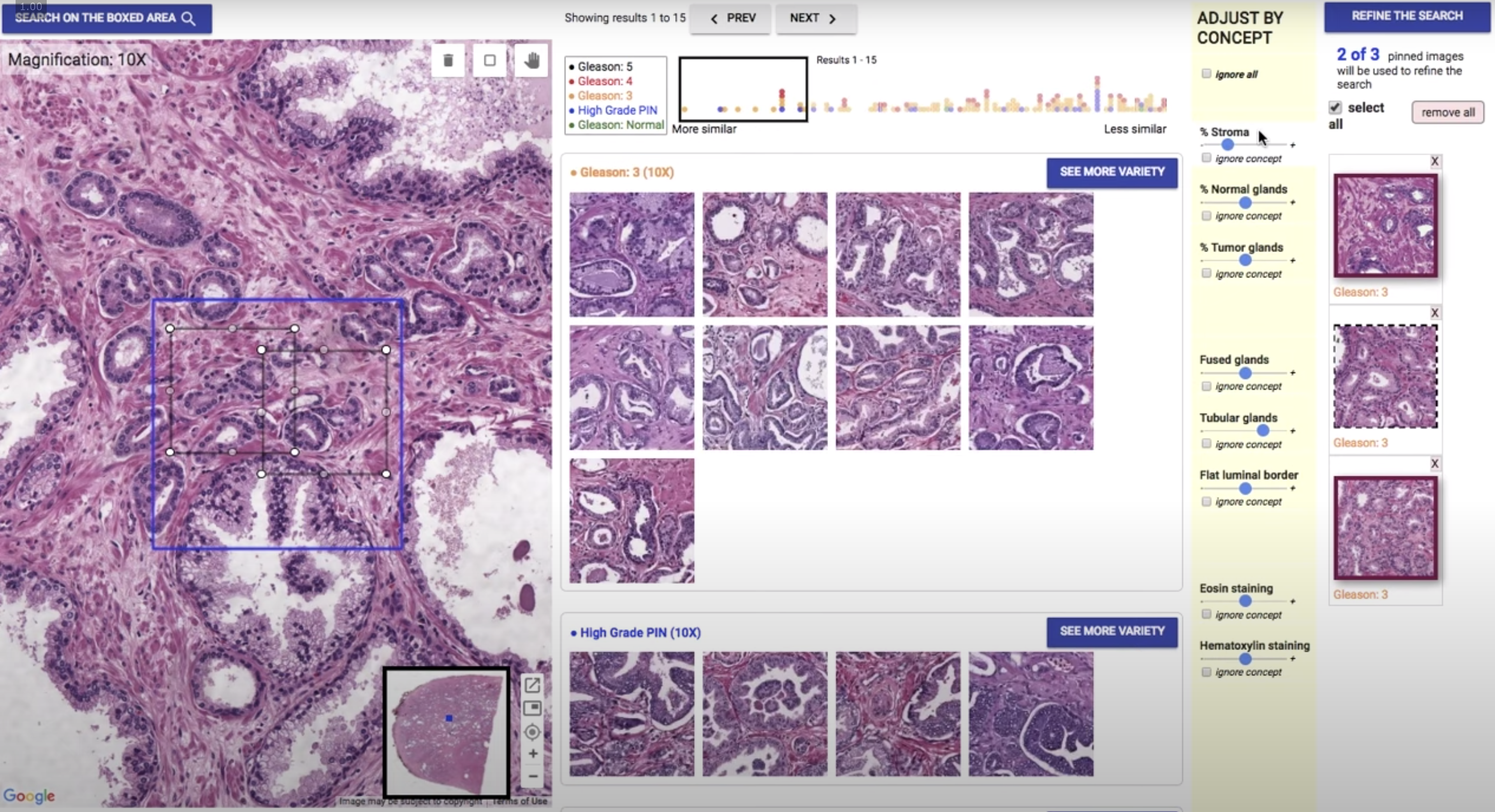

Tools that integrate into human workflows need to allow ways for people to specify what they want in more flexible ways. In clinical cases, doctors who use software tools to perform diagnosis may care about different features of a medical image at different points in time, based on their prior knowledge of an individual patient. Content-based image retrieval (CBIR) software that doctors use to look up similar cases from medical databases can get very good at returning “similar” results, especially when powered by ML. But a doctor often already has specific hypotheses they want to explore, as a user study on doctors’ use of CBIR systems discovered: “Maybe you might be interested in the inflammation at one point, but not right now. I would say. no I don’t want you to look at the inflammation, I want you. to look at everything around it.” Just like I might prefer Google results from small blogs one day and large, reputable journals the next, it’s nearly impossible for a global similarity ranking to capture the varied, case-by-case needs of each query.

Refinement tools recognize that the first result is rarely the best one, and allow users to “give feedback” to the model about what they want. A pathologist who wants to dig into a case where cellular morphology (as opposed to inflammation) is particularly important would normally have few options to specify this explicitly besides re-training a new model that distinguishes between the different kinds of cellular morphology.

In content-based image retrieval system SMILY (“Similar Medical Images Like Yours”), pathologists have the ability to refine-by-concept. By identifying which directions in the machine-learned embedding space correspond to human-interpretable concepts, the application can expose sliders that allow the end user to say “I want to see examples with more fused glands, to compare the diagnosis in those cases with this patient’s image.”

While the concepts are defined in advance in their prototype application, the method is general enough to extract concepts on-the-fly. We could imagine doctors labeling a small set of 20 or so examples for any concept that they might be interested in, and seeing the results adapt immediately.

The idea — allowing humans to directly specify the concepts they care about —is applicable in all sorts of applications. Legal technology companies aim to help lawyers, doing everything from extracting concerning clauses in contract review, to searching through large case repositories. Most of these products have yet to gain mainstream traction. Whether it’s because natural language processing results are far from perfect or because lawyers are slow to adopt new technology, the same ideas from SMILY can improve user trust and adoption while providing better results over traditional software. What if, instead of handing lawyers AI-reviewed contracts marked up according to some pre-labeled, implicit notion of what is important, we let lawyers specify concepts they’re interested in and worked with that? What if we not only used ML to return vaguely more relevant search results, but also created more levers by which they could specify what exactly they’re looking for?

Heuristics

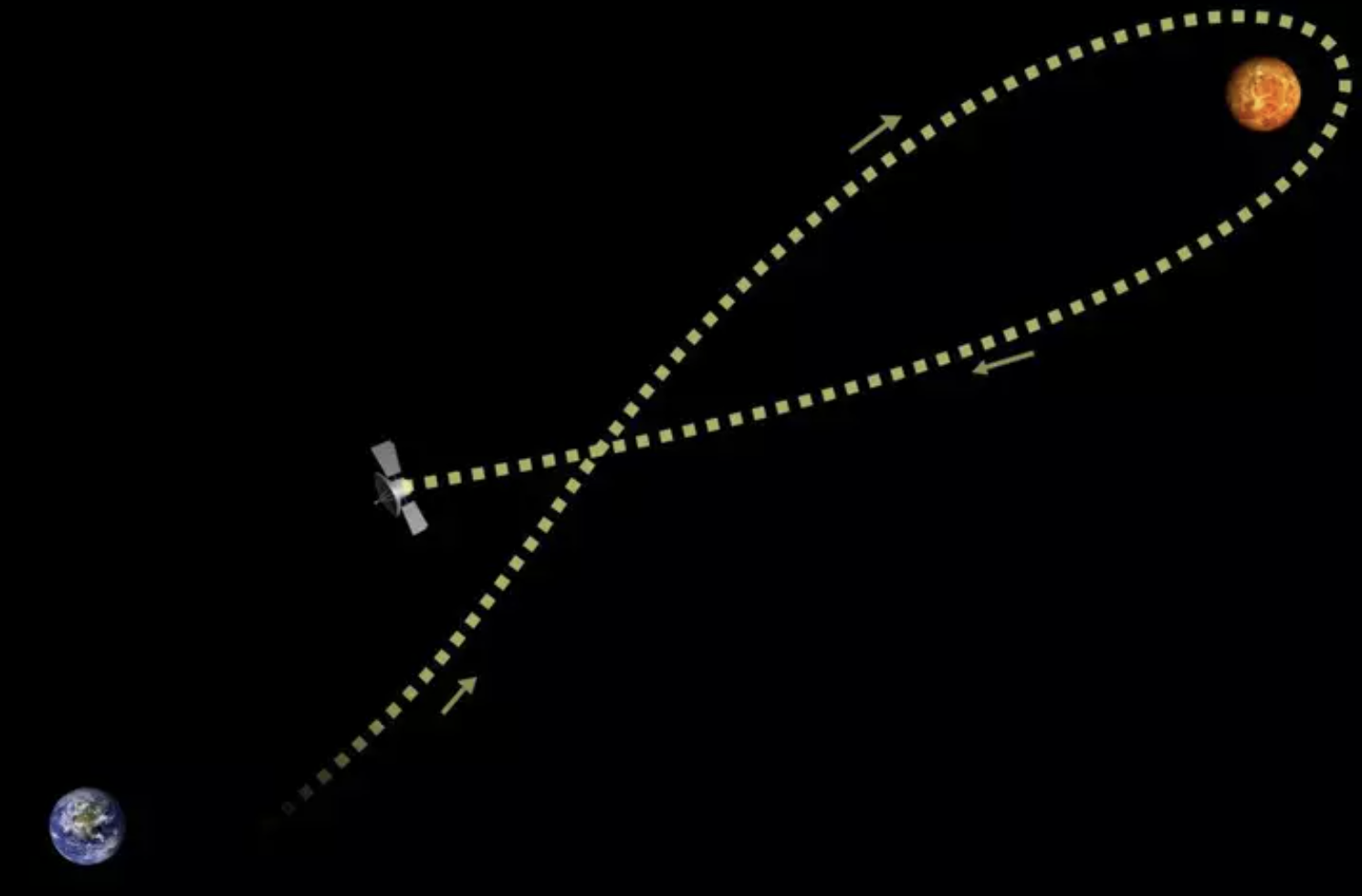

How do we get to Neptune, nearly 3 billion miles away? One way is to align your thrusters directly in the direction of that distant dot and burn away, slowly but surely. The other way is to take a bit of a detour. Voyager 2, launched in 1977, flew by Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus before reaching Neptune. In a maneuver known as a “gravity assist,” it used the gravity of each planet along the way to catapult it much further than it would otherwise be capable of going. In the vicinity of a planet, the spaceship could turn off its thrusters, fall toward the planet, and then swing around the other side, having stolen a bit of momentum without exerting any effort at all.

Just like in space travel, the best way to teach intelligent machines might not be to brute-force your way through a million training examples, but to create “interactional slingshots” that leverage how humans naturally do their work. We might design ways for doctors to structure their prior knowledge as our Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus — seemingly more work than just labeling “malignant” or “benign” on medical images, but if effective, ultimately more efficient in reaching accurate and robust diagnostic tools. End-users know what they want to achieve, and often have a partial understanding of how to get there. Instead of forcing users to specify this by labeling data points, we can change the inputs by using human preferences, constraints, and knowledge in the form they’re normally represented — as heuristics.

If we’re training a classifier to identify toxic messages on a chat forum, every data point labeled “toxic” is conveying “some feature of this message makes it so.” With enough examples, ML can eventually infer what those features are. It takes many examples to reach reasonable performance, though, and manual data labeling is slow, expensive work. On simple tasks, like identifying objects from images, companies can hire cheap, unskilled workers to label for $0.10 apiece. But for complex tasks that require expert knowledge, like identifying fake news or extracting clauses from legal documents, it becomes prohibitively expensive to do at large scale.

A human mind labeling these chat messages chugs through an analysis pipeline of its own: this message has curse words — toxic. This message written in all-caps is probably aggressive, so unless it’s expressing excitement — toxic. Heuristics like these allow us to simplify questions to arrive at a quick conclusion with minimal mental effort. As Nobel-winning psychologists Kahneman and Tversky famously showed, heuristics are pervasive in human judgment and decision-making, from our day-to-day judgments of people to a legal expert’s evaluation of whether a contract is problematic.

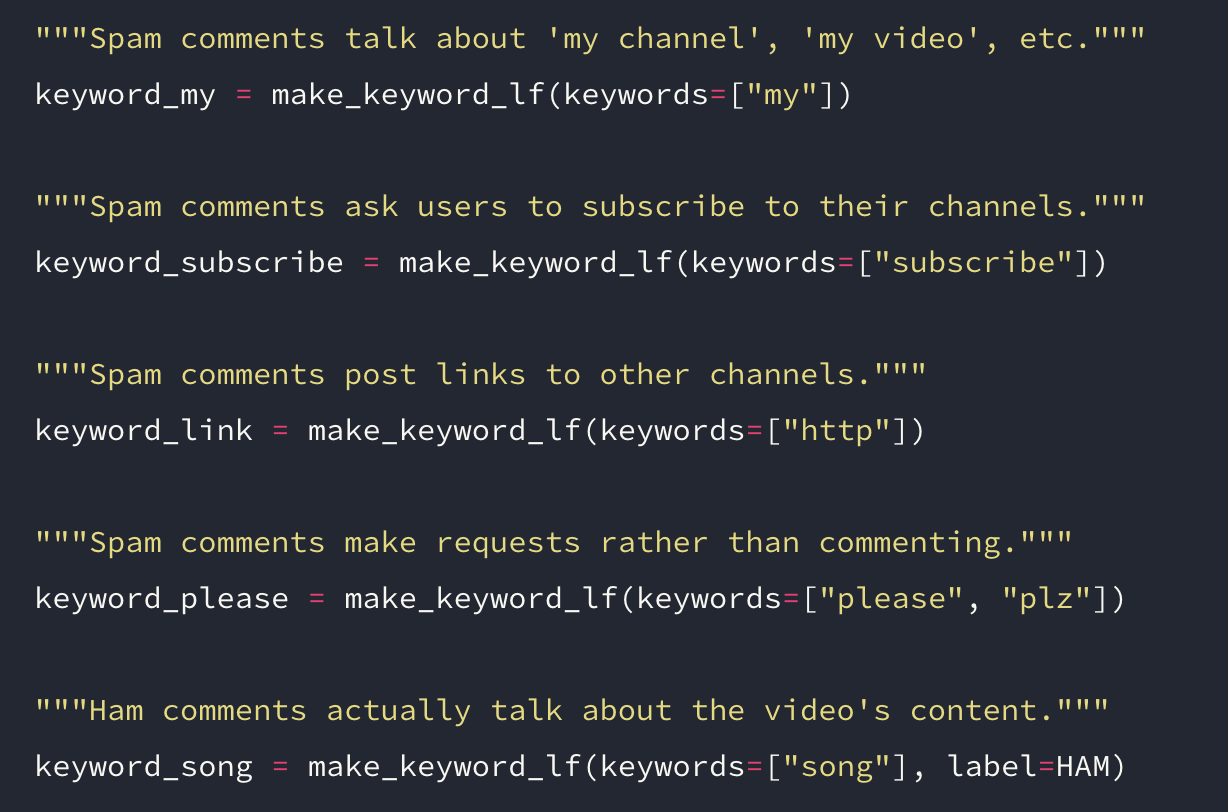

Instead of having humans mentally translate heuristic judgments into data labels, we can build tools like Snorkel to do so with methods for weak supervision. In this setting, instead of assuming we have a labeled dataset, we start from an unlabeled dataset and combine it with noisier sources of information like heuristic rules. By peering at some unlabeled examples, we can train a classifier for whether a given Youtube comment is spam or “ham” (relevant), using simple insights from looking at a couple of examples:

# Spam

[

"Subscribe to me for free Android games, apps..",

"Please check out my vidios",

"Subscribe to me and I'll subscribe back!!!",

]

# Ham

[

"3:46 so cute!",

"This looks so fun and it's a good song",

"This is a weird video.",

]Spam comments tend to advertise for other content, and they tend to say “my channel” or “my video.” From there, the rule-writing is easy: just look for certain keywords. Beyond keywords, perhaps spam comments tend to contain more misspellings, in which case we can program a rule that runs each message through a spell-checker.

Using heuristics is much less reliable than labeling each point individually. They might not always hold (someone might say “this is my favorite song,” triggering the first spam rule). They might contradict each other. Instead of requiring logically consistent rules, the value of a tool like Snorkel lies in recognizing that people think in terms of structure, but not perfect structure. Snorkel accounts for the noise, aggregating different rules statistically to resolve the final label for a given comment. The human is simply able to provide more high-level, interpretable, natural input. The rest is left up to the machine.

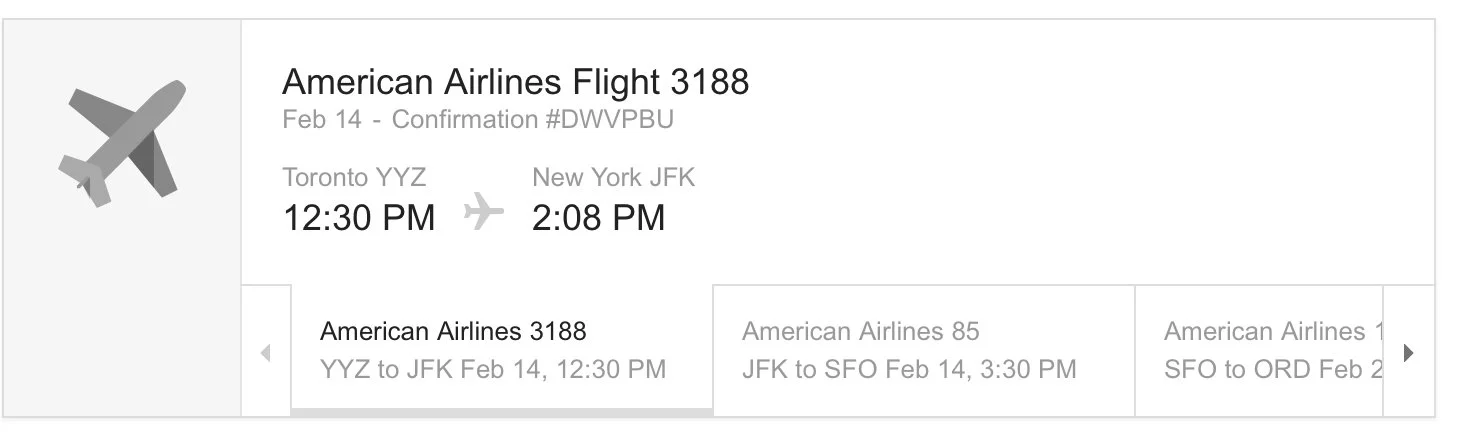

Because humans think in terms of heuristic rules, many of the resources and systems that exist today have rules embedded into them. Since 2013, Gmail has used hand-crafted rules to automatically extract structured information, like flight details, from emails. There are several different verticals of interest — bill reminders, shipping confirmations for online purchases, hotel reservations — and each of them requires different fields to be extracted. The email templates are similar within each domain, but not identical enough for there to be a catch-all solution. From a paper describing their legacy system:

In the same paper, the Google team describes how they used Snorkel to migrate this rule-based architecture to a more powerful ML system. Instead of throwing away their existing system and manually labeling a set of examples from scratch, they can use the rules to bootstrap a high-quality, ground-truth training dataset.

Tools like Snorkel can position themselves differently from other ML companies: it’s not just that it can develop a better system for extracting flight details from data, but it can do it with knowledge that a company has already created naturally. Few people will understand the value of “we’ll replace your current system with a machine learning solution”; many more people will understand “you already write rules. We can use the same rules to do better.”

The current control surfaces for AI are crude, in the sense that there’s really only one way to tell a machine what we want it to do: with a labeled training example. A labeled training example encodes a world of information: domain-specific knowledge, ethical desiderata, and business goals. We hope that machines can infer what we want, but we have few ways to explicitly specify these concerns.

If we build interfaces that translate between the language of humans — concepts, constraints, and heuristics — and the language of machines and data, we can leverage the best of both. We can achieve better performance on tasks, because it’s much easier to collect data when humans are just doing what they naturally do in the course of their work. We can have more certainty that the objective functions that machines optimize are aligned with the objectives of humans, because we’re directly specifying the concepts we care about.

Change the outputs

Simulation and understanding

A rare cell population — just 7 of every 10,000 human B-cells, the cell type responsible for secreting antibodies — is surprisingly critical. This subset of B-cells is responsible for “checkpointing” that a particular progression of DNA recombination occurred properly. And when this tiny subset malfunctions, it’s responsible for pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the most common type of cancer in children (Good et al., 2018).

It’s a common theme in science: often, the most rare events are the most critical to understanding a natural system. Most machine learning tools, on the contrary, are designed to predict an outcome in the average case. As computational biologist Dana Pe’er commented: “common machine learning approaches might give you all the best scores on all the favor[ed] metrics and you would still miss the discoveries that matter most.”

In science, the goal is never just to fit the data with a model, but to derive some generalizable insight from this process. René Thom said prédire n’est pas expliquer: “to predict is not to explain.” ML models are apparently the antithesis; by normal design, they excel at prediction but remain “black boxes” impervious to interpretation or explanation. Still, there is a place for them in rigorous science if we change the outputs — instead of predicting results directly, what if they were used to produce artifacts that could help humans better understand the problems themselves?

Simulation, in particular, is fundamental to how people understand the world. In science, simulations of the natural world allow us to observe how simple mechanisms like metabolic interactions can give rise to emergent phenomena like disease. Some cognitive scientists even postulate that simulation might be the engine for human reasoning — children might develop common-sense physical intuition by learning to simulate, for example, whether a stack of dishes will fall. Using simulation to observe how a system evolves is particularly game-changing for science, where the raison d’être is understanding itself. But even beyond science, tools that help experts and laymen alike understand a system are often more valuable than ones that attempt to solve a problem directly.

Take the history of economic policy as an example. Washington bureaucrats began embracing economics in the 1960s, hopeful that the rigorous theory and experiments of academic economists could help manage the buffet of interventions available to the government.

Setting tax rates, controlling the money supply, managing the employment rate: all these levers have drastically different effects on American prosperity. The challenge is that all of these levers operate within a highly complex and interconnected system. Increasing government spending spurs demand; decreasing government spending curtails inflation. Every intervention presents a reasonable logic as to why pulling lever A with method B will produce certain economic outcomes. And every intervention has seen surprising tradeoffs and unintended consequences when put into practice. The question of which interventions (if any) are the most effective at improving quality of life is hotly debated to this day.

Much like the endeavour of science, we need understanding. It isn’t enough to aim for one goalpost, whether it’s lowering unemployment or lowering inflation; policymakers have to navigate the system, understanding and trading off one factor for another, while accounting for factors entirely external to the economic system: public opinion, diplomatic relations, and more. And when faced with entirely new situations (say, a pandemic hitting the global economy), an understanding of all the levers available to us will be what determines success.

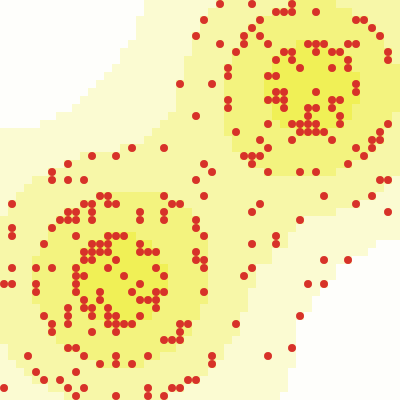

Eric Beinhocker argued in The Origin of Wealth that many of the same tools used to understand scientific phenomena can be used to understand the economy. Instead of viewing the economy as a static, equilibrium system as in traditional neoclassical theory, analyzing it as a complex, adaptive system, with many independent agents interacting in an evolving system, might result in emergent patterns that match reality much more closely. One of the first large-scale “complexity economics” models was Sugarscape, developed in 1996 by Joshua Epstein and Robert Axtell. In Sugarscape, agents (red) inhabited a two-dimensional grid, each cell with varying amounts of sugar (yellow). At each step of the simulation, agents can look for sugar, move, or eat sugar. All agents have a natural “genetic endowment” for vision and metabolism, and a random geographical starting point. The simulation begins with a typical bell-shaped distribution of wealth — with a solid middle class and few agents very rich or poor. By the end, the distribution has transformed dramatically, with an emerging super-rich class, a shrinking middle class, and a swelling bog of poor agents.

Even with simple assumptions, the simulation is an illuminating way to understand how individual behaviors, combined with some luck and predisposition, result in emergent, macro-level outcomes for inequality.

Agent-based modeling caught some wind around the 2008 financial crisis, with articles published in The Economist and Nature decrying traditional economics’ failure to predict the global financial meltdown. With hope, they speculated that “the field could benefit from lessons learned in the large-scale modelling of other complex phenomena, such as climate change and epidemics,” adding that “details matter” in modeling the entangled interactions in the financial sector and incorporating the psychological insights gained from behavioral economics.

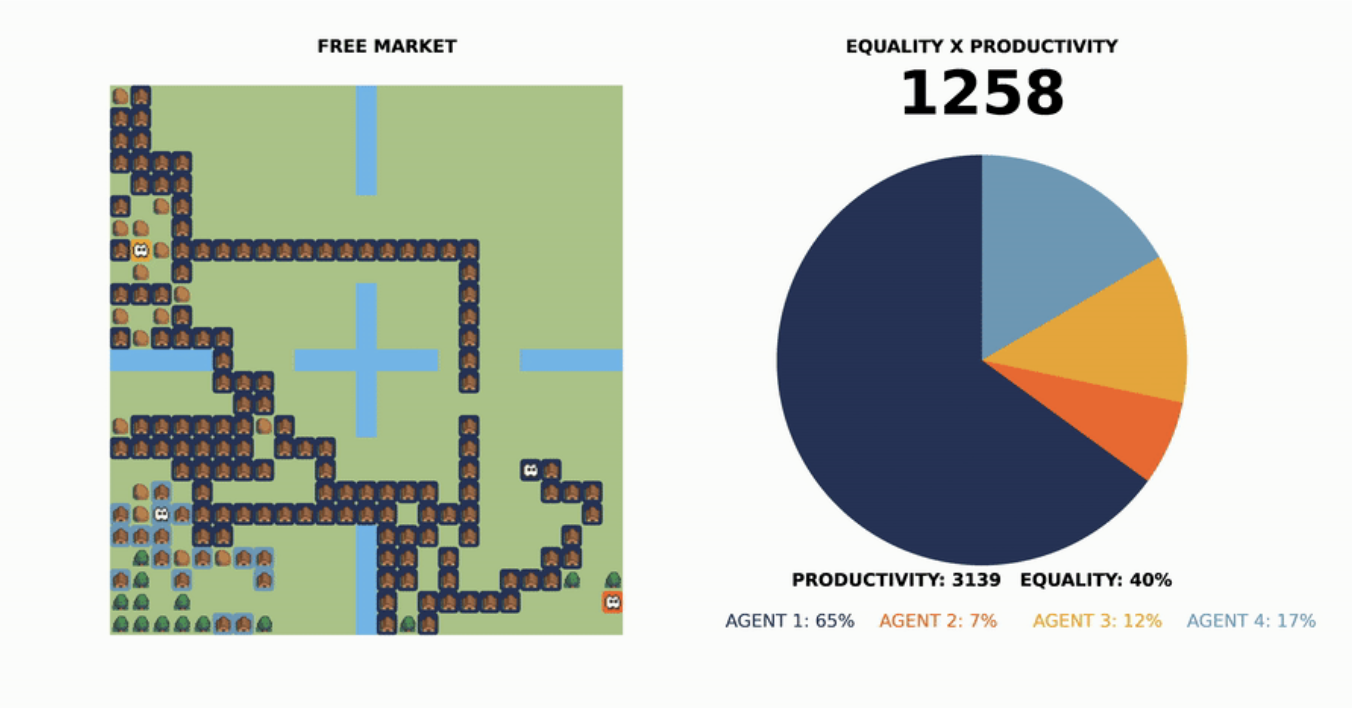

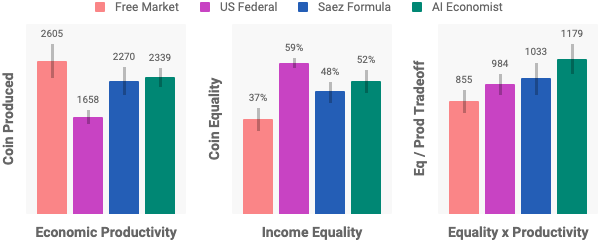

By using machine learning as the backbone for these sorts of simulations, we might be able to create increasingly realistic and powerful simulations as tools for decision-making. A recent collaboration between Salesforce Research and economists applied reinforcement learning to tax policy design to create the “AI Economist.” Reinforcement learning agents learn to take actions that maximize a particular reward through trial and error. In Sugarscape, we could only simulate simple strategies; agents acted greedily at each timestep to maximize sugar intake. With RL, agents can learn more complex strategies. Allowing the ability to trade, the agents display emergent specialization, with agents with lower skill becoming “gatherer-and-sellers” and those with higher skill becoming “buyers-and-builders.” They learn to “game” tax schemes by alternating between high and low incomes in a way that lowers their average effective tax.

RL can also be applied at the policymaker level, to learn the “optimal” tax schedule to maximize a particular goal while adapting to the emergent behavior of the simulated society.

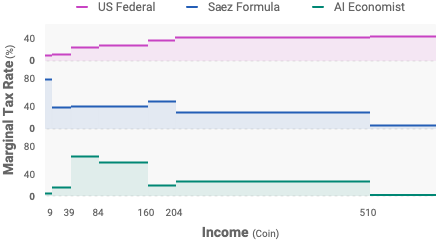

“Ideal” tax schedules optimized for equality and productivity look qualitatively different from those proposed and implemented today. Surprisingly, even though learned tax policies are tuned to the behavior of the artificial agents, in experiments with human players, they also maximize overall equality and productivity compared to other tax schedules. It seems to suggest that the simulation reflects at least part of real dynamics in human economic decision-making.

To be sure, the tax schedule is not intended to “solve” the tax policy design problem. The simulation is still a relatively simple model of the economy, with many social, political, and economic factors that are not captured at all. But the idea of simulation is to allow policymakers to study the effects of policy and incentive design at a different level of complexity and realism that we do not see in traditional economic research.

Whether an economic system or an Internet platform, ML-driven simulation provides an opportunity to study behavior and interventions that would otherwise be infeasible in the real world. Facebook Research recently published a paper on Web-Enabled Simulation (WES), its custom simulation of how users might interact with the platform and with each other. They can train bots to mimic simple human behaviors and observe how Facebook might enable or impede certain kinds of actors.

For example, some bots might be trained to act like scammers; by setting a reward for finding other users to exploit, reinforcement learning algorithms eventually discover which actions to take to maximize the scammer’s reward. Facebook can then study how platform incentives or loopholes in the software design help scammers thrive, and how other (e.g. scammer detection) algorithms can curb this behavior.

Just like software testing ensures that code follows a particular specification, so-called “social testing” with sophisticated bots might ensure that the platform has safeguards against undesirable emergent social behavior: scamming, exploiting privacy loopholes, posting bad content, and more.

ML-driven simulation reframes an alternative use for ML: beyond predicting answers or solving tasks directly, we can use it to drive tools that enable human understanding. Increasingly intelligent agents in simulation allow us to play, tinker, and experiment in a realistic sandbox, combining the best of our understanding of the world with the best of ML.

These kinds of tools for understanding leave the formulation of the problem more open-ended. The prediction approach to the problems above would be optimistic — perhaps, if we just trained a ML system to “find the tax policy that maximizes equality x productivity,” it would just spit out the camelback schedule, and we’d implement it to great benefit. But, more likely than not, after putting it into practice we’d discover that we didn’t understand what we wanted after all: we might want to maximize equality x productivity, but only if it doesn’t cause extreme poverty for certain groups. Facebook might want high click-through rates, but not at the cost of increasingly polarizing content. Simulations and other tools for understanding are only partly solutions and mostly richer ways to discover what we want. The hard part might not be optimizing for the objective (what the machine does), after all, but figuring out what objective we want in the first place. And for that, we’ll always need a human in the loop, building an understanding of the system with the help of the machine.

III / Why interactivity?

To re-contextualize these new directions, we might ask — when do we need more advanced interactivity than humans-as-backup?

To be sure, humans don’t need to be deeply involved in every application of ML. Managing data center cooling or categorizing product images, for example, seem like purely technical problems that don’t require humans. And of course, every company strives for scale — Google Translate handles 140 billion words per day, and it’s neither smart nor feasible to expect human labor to achieve the same scale.

Humans-as-backup is essentially a system on its way to full automation. Through that lens, humans-as-backup systems are useful when:

-

We’re close to the performance and reliability we need

Systems that start as humans-as-backup expecting just “a little more” data collection to reach success are taking a huge risk. We just don’t know, for a specific machine learning application, exactly how much data is needed to reach a certain level of accuracy and reliability. We might have a Moore’s Law-like explosion of capability, or we’ll be left labeling examples until the money runs out.

Self-driving cars have been projected to be “on the horizon” for decades. Today, still, despite all the resources being thrown at the problem, we’re still far from seeing reliable performance. Those in the industry have shifted their consensus opinion to “at least 10 years away,” and as Starsky Robotics founder soberly reflected, “there aren’t many startups that can survive 10 years without shipping.” This theme emerges in many AI applications, as a16z describes.

A few elements might give us confidence that we could be looking at an exception to this kind of ever-growing delay: the problem is a standard ML task (e.g. labeling images), we have a good grasp of the scope and edge cases of the problem, or we simply don’t need the highest quality or reliability (e.g. Google Translate). In these cases, humans-as-backup can work as a temporary milestone on the way to full automation. For other situations, building systems that include humans by design may be more effective.

-

The objective is really all there is to the problem

As we’ve seen with recommendation algorithms, translation, and other examples, usually the outcome we want requires us to build on top of the machine’s task in isolation. Youtube users want to be recommended videos they like, but also have a chance to explore new interests, not watch too many distracting videos, and may have a whole host of other desires that aren’t captured by a single metric of the system.

Often, there is more to the task than what the machine is doing: adapting the larger needs of the system into machine-readable inputs, translating the machine output into practical insight, or handling the inevitable exceptions and side effects that come from misalignment between human and machine objectives. By design, interaction accounts for how humans will need to interface with the machine in these cases. Otherwise, humans-as-backup is well-suited for mundane tasks or pure optimization with clear objectives.

-

Machines should be responsible for this task

While the popular question has so far been “what are humans uniquely good at?,” perhaps the more appropriate one is rather “what should humans be responsible for?” In other words, just because a machine can do a task doesn’t mean it should; in many cases, humans should preserve the ability to make decisions, set goals, or otherwise exercise agency over how things go.

This is most apparent in AI fairness problems. Using machines to predict who should get hired or who should go to jail poses obvious concerns about reinforcing historical bias. But problems of agency appear in more subtle places, too, like recommendation algorithms that determine the information that people consume. Interaction provides a way for people to understand and intervene in systems that affect them.

Most applications don’t have the good fortune of landing at the intersection of these three conditions. For conversational bots, virtual assistants, high-stakes medical applications, legal document analysis, and more — humans might be in it for the foreseeable future.

Figuring out what kind of interaction works best for each of these applications is still a bespoke process, dependent on the details of the tool and users. We don’t have a unifying framework like we do for systems design or user interface design. In the future, we might have design patterns for systems of humans and machines like we have dataflow programming, microservices, and other patterns for systems of computers. This is not to say that humans should be seen as machines, but that we’ll have an understanding of what humans need in their own right, and a more complete picture of the design possibilities — the loops, inputs, and outputs — to accommodate them.

The design space will expand as research progresses. There are a lot of relevant, exciting research areas neglected in the examples: much of reinforcement learning, including new methods allowing machines to learn from human demonstrations or corrections, for example; imitation learning; natural language-guided learning; interpretability and explainability; as well as all the work that has been done on expanding the range of tasks and reasoning that machines can carry out. But the idea of the new directions outlined here is to decouple interactivity from “intelligence.” We might think interactive ML will come naturally with more advanced machine intelligence — perhaps, imagining that smarter machines will truly be able to converse with people like the HAL-9000’s and Samanthas of science fiction films. In fact, the most impactful advancements in human-computer interaction have looked nothing like intelligent, conversational, human-like machines. They have been devices and software designed with simple ideas, like the mouse and keyboard, GUIs, hyperlinks, spreadsheets and word processors.

Charting out interaction paradigms in new applications will be hard, but the systems that do so successfully will be better tools and products. They’ll attract the best people, since doctors, lawyers, translators, and other domain experts want to work with technology that meaningfully uses their expertise. They’ll power higher-quality services, since they leverage humans more effectively. They’ll form a more sustainable foundation to improve over time, since they can draw from rich interaction data and support humans from day one.

With feedback and open-ended interaction, they’ll demonstrate a richer range of behaviors than machines designed simply to complete the task. They’ll be closer to the vision of “man-machine symbiosis” first articulated by the computer pioneers than we have ever been before.