With the explosion of computer use agents like Claude Computer Use and search wars between Perplexity, SearchGPT, and Gemini — it seems inevitable that AI will change the way we access information. So far, we’ve been obsessed with building agents that are better at understanding the world. But at this point, it’s important to realize that the world adapts itself to LMs, too. Codebases, websites, and documents were made for humans, but they start to look different once LMs become “users,” too.

In this post I’ll explore some emerging signs of what this future might look like – how is the world adapting already, and what might the Internet like at the end of it all? As a researcher or developer, this poses some interesting questions. If we realize that the digital world is fundamentally malleable, the line between “agent” and “environment” starts to blur. Instead of building better models, what end-to-end systems should we be building instead?

How it begins

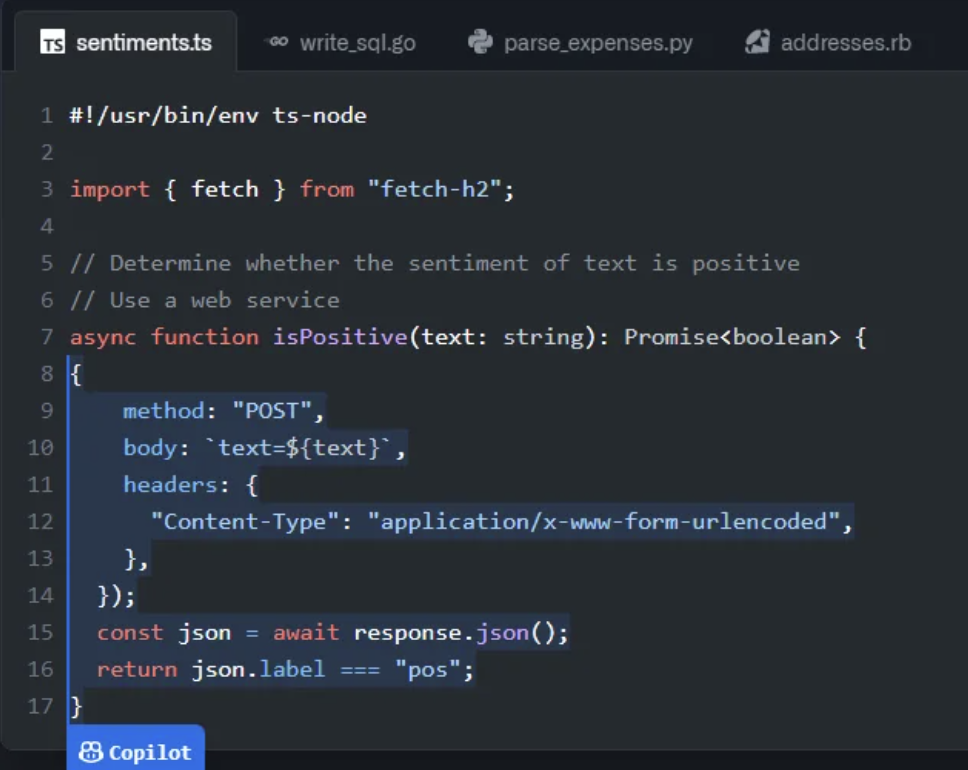

When I code side-by-side with GitHub Copilot, I often notice how my behavior changes in subtle ways to adapt to the tool. Code autocomplete naturally lends itself to “docstring-first programming” — you’re much more likely to get a helpful code snippet if the model has some description of what you’re trying to accomplish first. So naturally, you might type in a comment or a descriptive name first, and then pause to see if you get the right snippet back:

Put simply, to make Copilot work better, you can make the code look a certain way. The end result is that the codebase ends up looking more chunk-by-chunk commented than it otherwise would. Code written for human comprehensibility looks different from the one that emerges from programmers micro-optimizing for LMs. The environment adapts to the tool.

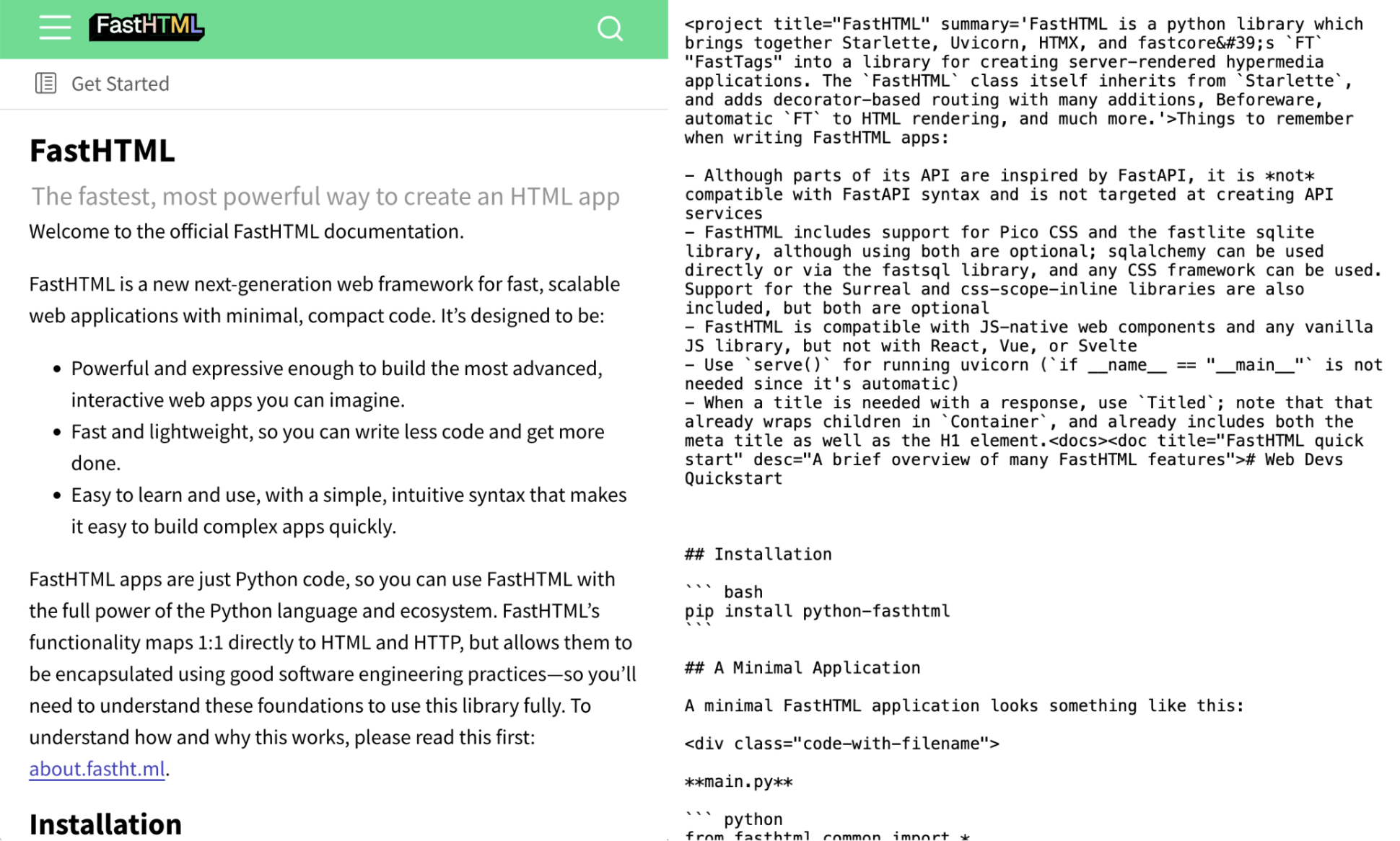

More interestingly, this adaptation is happening beyond the code we write. As a library / framework / tool developer in 2024, you can bet that a good portion of your human users will be interacting with your framework via their coding assistant. Being “dev-friendly,” i.e. building for the workflow that users have, means building for their LMs. FastHTML from Jeremy Howard, for example, includes llm-ctx files — docs intended for LM rather than human consumption. It’s the inklings of a new, parallel world built for LMs.

Agent-computer interfaces

The same principle appears across many applications — to make LM agents work better, give it the right context in a format it can understand. We want LMs to operate on websites, GUIs, documents, spreadsheets, and more. Already, for each of those environments, a hidden part of modeling is actually adapting the environment, massaging the input so that it’s more comprehensible to the LM.

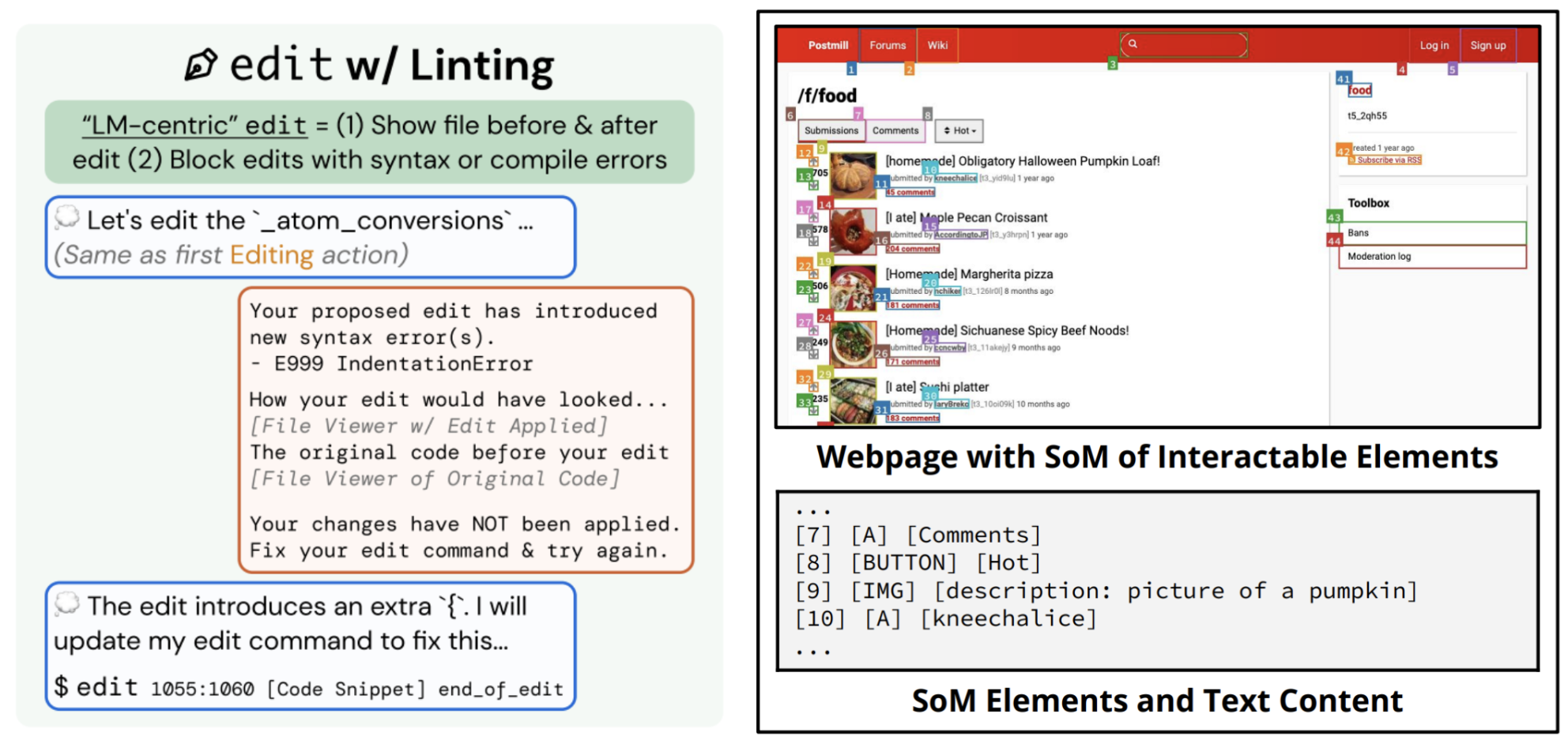

SWE-agent first made this case explicitly: by building an “agent-computer interface,” a layer on top of the file viewer, editor, terminal, etc. for a computer-using agent, you can get huge performance boosts. Short of end-to-end pixel-based control, these design decisions are in every agent: for instance, even for multimodal agents, it helps to augment the UI with high-level interactable entities and actions so that web agents can just output “click element [36] [A] outdoor table lamp” (instead of <a class='_quad-multi-linkContainer'...>).

The reason why we have to do this is because UIs are designed for human users. We create webpages with design principles like visual hierarchy or “F-shaped pattern reading” because we discovered humans have shared biases in how they process visual content. LMs have no such priors, so we just end up baking the same inductive biases back into the model, teaching it through lots of data that e.g. “if an <img> icon is to the left of a form field, they’re probably semantically related.”

When we step back, this feels roundabout — I have some underlying data I want to show to a user, so I design an interface that communicates that intuitively to them. Now, instead of a human seeing that UI, we spend a lot of time building a model to effectively parse out that visual information back into the underlying data or API request. (Hm… 🤔)

We have increasingly sophisticated models and tooling to do this kind of “postprocessing” of human interfaces for LMs, like converting an HTML webpage into Markdown or encoding spreadsheets to be more digestible by a model. This will certainly be useful in the near-term because most websites won’t be natively adapted to LMs for a long time. But I’m pretty excited about work pushing the alternative approach further. If the raw data in spreadsheets is more often manipulated by an LM than by a human at some point, what if we made a spreadsheet for a language model from the ground up? Or a computer OS? And then what would the human interface look like at that point, once we leave the low-level manipulation to machines?

In other words, we can improve how well LMs use human interfaces in two ways:

- Make the LM smarter (e.g. better reasoning, multimodal understanding)

- Make the interface easier for LMs to understand

I think these are two distinct bets: one, where sufficiently intelligent LMs can just be slotted in where humans are, using the same interfaces; and two, where LMs will just be “something different,” with their own ecosystem and comparative strengths. Which approach will dominate in the long term?

From a research perspective, (1) is appealing because it’s foundational. If you care about AGI, “using a computer” is just a testbed for intelligence.

If we care about useful agents, (2) feels underexplored. LM interfaces may seem ad-hoc today, but there’s no reason that they can’t be just as general as human interfaces if we commit to bet (2) (e.g. build the OS). And there are distinct benefits: efficiency (e.g. function calling vs. multimodal pixel control), safety (limiting the set of actions available to LM interfaces), and a wider design space (parallelization without spinning up 500 VMs). Unlike the physical world, which we have to model with general methods because nature just is a certain way, we built the digital world. And we can build it differently.

The world changes when we build tools for it

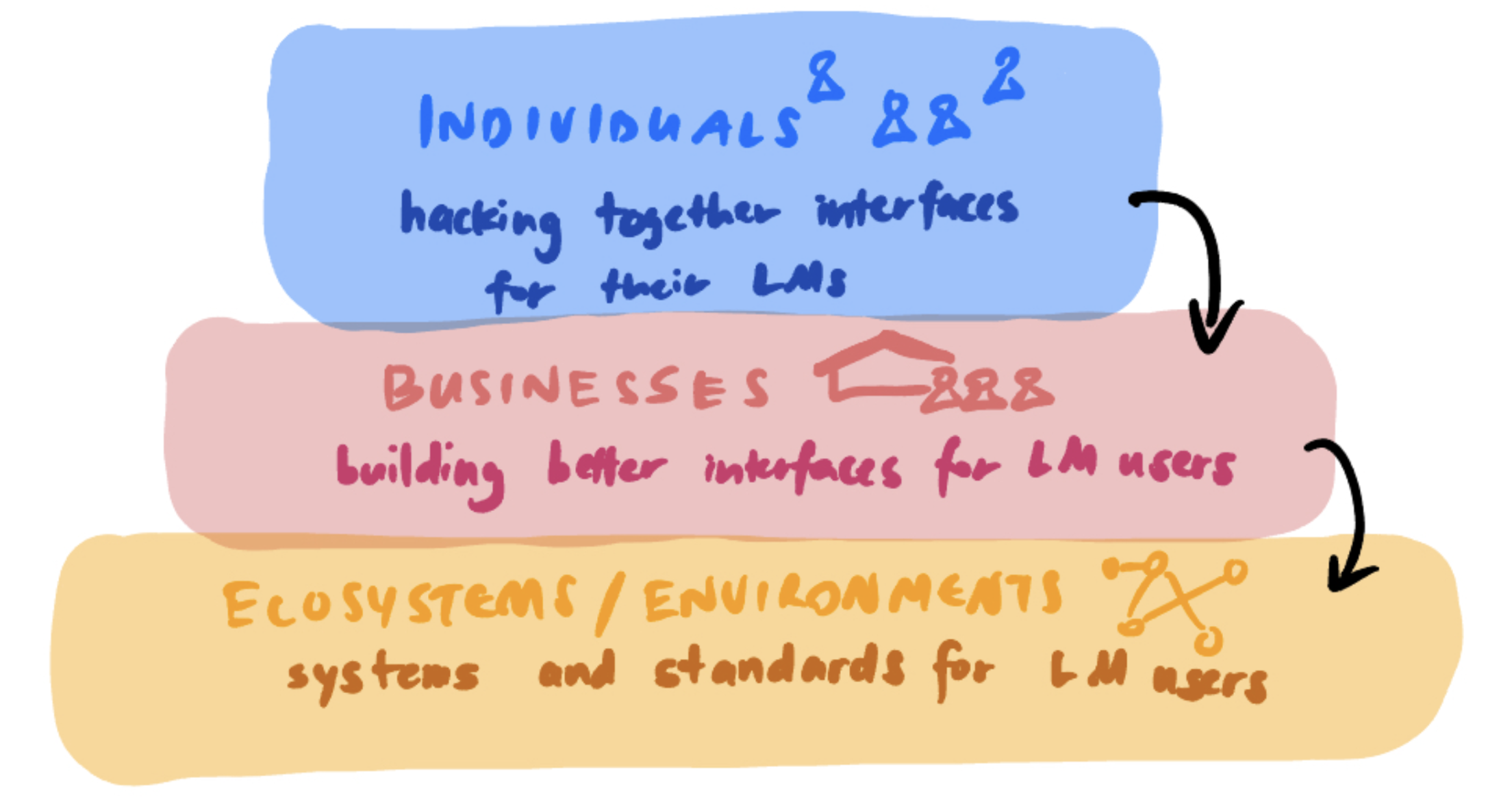

When a new technology comes along, individuals are often the first to change their behaviors. Many of the instances above are individual teams of researchers and engineers figuring out prompting schemes or hacking together APIs / agent interfaces for their LMs to work better.

Then you notice businesses and providers adapting: as more people use language models to interact with their devtools, for example, it makes sense to write docs for LMs. We’re not there yet, but it’s not hard to imagine that if web agents actually become a widespread utility, it makes sense for websites to make their UIs slightly easier to parse so they’re more usable by LMs, and then maybe then to build full-fledged products that are designed for compatibility with LM agents. Before you know it, the Internet starts looking different.

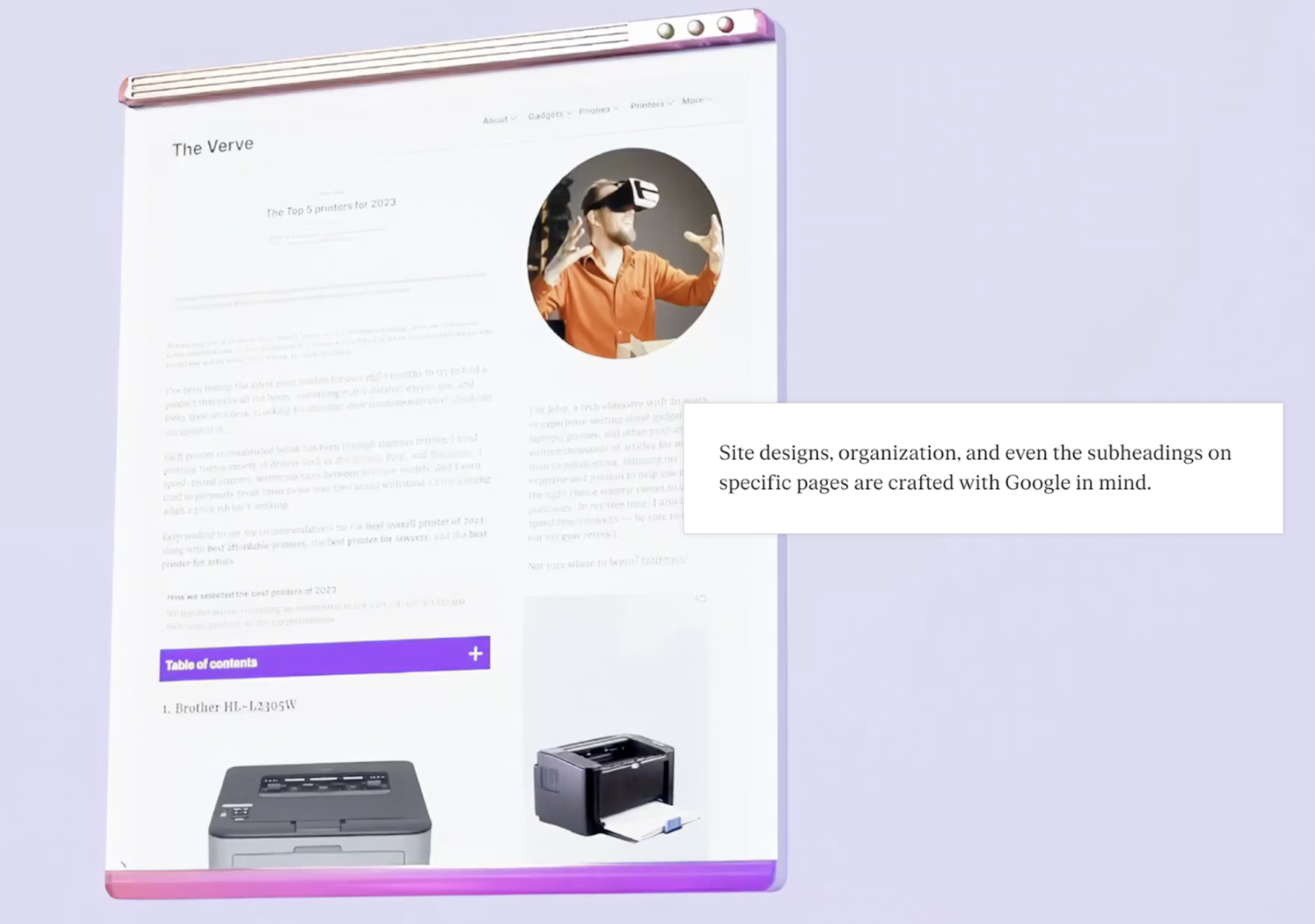

This story sounds familiar: search engines are one of our primary interfaces to the Internet today, and they’ve certainly changed the shape of the Internet since the 1990s and 2000s. PageRank was an effective algorithm because it identified useful heuristics for finding high quality websites then; primarily that “more important websites are more likely to receive more links from other websites.” But as Google gained popularity, it wasn’t just that they adapted to how the Internet was, but websites adapted themselves to Google. The formats and content that PageRank understood to be “high quality” were built more often. Sites became more standardly templated. People put entire essays and FAQs before the actual recipe. And so on into the SEO-optimized Internet we have today.

What will the web look like when LMs become one of the standard interfaces, whether through chatbots like ChatGPT, AI search engines like Perplexity, or web agents? I think it’s an interesting future to speculate on, but maybe more importantly, what we anticipate can affect the things we build today. People who develop agents might see the Internet “environment” as fixed, but in reality, the entire digital world co-evolves with the tools we build. And given that agent-computer interfaces do seem like an underutilized lever (vs. the popular orientation towards general agents using human interfaces), there’s a lot of unexplored territory. For one, we don’t actually know what kind of interface will be best suited for LMs. I’m pretty excited about research that tries to understand and distill the “design principles” that drastically improve performance and utility of models today. It’s a systems-building approach to AI research: instead of just improving models in isolation, we can expand our view to improve the systems they operate in as a whole.

How will human interfaces change with LMs?

Considering how the world will adapt to LMs also might change what applications will be useful. LMs don’t just provide a window to the Internet — in some cases, they might “replace” some functions of the Internet entirely. If I have a personal AI agent, do I still go to OpenTable to book a reservation, or fill out forms ever again? Once I get “generative answers” synthesized from an LM reading the web, do I still need to go to the webpages myself?

I don’t think humans will get all their content through a LM — and then the interesting question is which parts of the web will primarily be for LMs vs. humans.

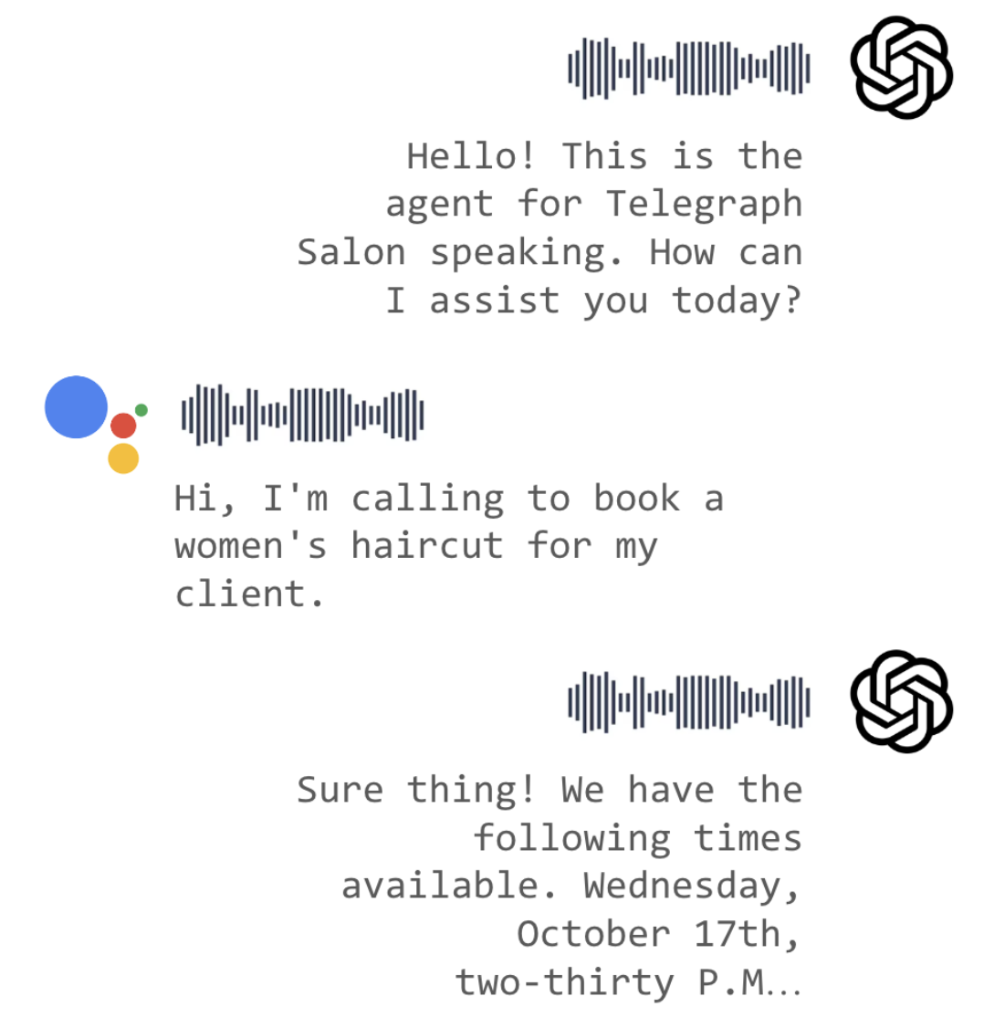

It does seem like a lot of applications are optimized for the near-term without taking a stance on this question. For example, today, people are obsessed with voice interfaces (perhaps also because they’re “general”), with applications like agents for businesses to take calls or field customer service requests from customers. But voice is a good interface because it’s good for humans. When you realize that we’re headed toward a future where the customer also has their own Google Assistant to call the business, and they have to do this all robustly… we might be making the problem more difficult than it has to be.

In the long term, we should ask what humans will still have to do. I hope that calling in to reschedule my package delivery isn’t something I have to do manually in 10 years, and if so, then maybe we don’t need to keep building around a fundamentally human interface (voice) to solve this problem. The “thing I want done” is not “making a phone call to the doctor” but “booking an appointment,” and if technology can coordinate appointments, then no one needs to take a call after all. We build LMs to help people do things, but we do a lot of the things we do because we don’t have AI.

This isn’t just about UX/graphic design of interfaces, but fundamentally a question about what work will be done by LMs vs. humans. If LMs can indeed handle a lot of the low-level action and information synthesis we do today, then we’ll need new interfaces for humans to do something else — maybe the high-level management, or specification of what we want, or some other fundamentally human communication. Sometimes, I don’t just want the LM to tell me the answer, but I want to read the experiences and look at the photos from a human who actually did something in the real world. Once LMs handle the tasks for machines, maybe new tasks and new content, for humans, will emerge.